As is often the case with named items of militaria, a little bit of digging can reveal quite a story. That’s certainly the case with this Victorian era Lancers Officer’s Undress Frock.

The Frock was designed to be worn in the field and on campaign, as an alternative to the more elaborate tunics usually sported by the Cavalry. These differed slightly from regiment to regiment, as each made small changes to customise them into a regimental pattern. This particular example to the 16th (The Queen’s) Lancers has the standard 16th Lancers regimental buttons, but the addition of blue piping to the arms, front seam and the rear. Instead of shoulder straps, a golden cord strap is used and blue pointed cuffs and collar have also been adopted. This is a very rare surviving example.

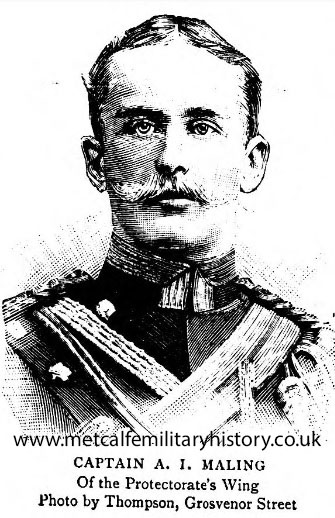

The name label inside has become faded over the years, hardly surprising for an item of work-wear that’s near 130 years old. However, the surname is evidently ‘Maling’ and although the initials are a little harder, only one officer by this name served with the 16th Lancers during this period. Having identified “Arthur Irwin Maling” as the officer, the initials match up, despite the ‘A’ initially looking like an ‘H’.

Lieutenant Arthur Irwin Maling – 16th (The Queen’s) Lancers

Arthur was born in Liverpool on 10th May 1870 to Captain Irwin Charles Maling (23rd Foot) and Emily Ann Maling. Unusually, he was then baptised in Speldhurst, Kent. The following year, the family travelled to Australia, where Captain I C Maling was appointed as the private secretary to the Governor of Queensland. A few short years later, Captain Maling became private secretary to the Governor General of New Zealand.

Arthur was educated at Cheltenham College, where he was part of the Gymnasium VIII and Football XV. Following in his father’s footsteps, Arthur attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst and was commissioned into the 16th Lancers in October 1890. At the time of his commissioning, the 16th Lancers were in India, so in December 1890, Arthur boarded the troopship ‘Malabar’ from Portsmouth to Bombay with 4 other newly commissioned officers of his regiment.

By 1893 Arthur would have likely settled into army life in India, and in February attended at Old Cheltonians dinner in Lucknow. In July 1894 he was seconded for service with the Army Service Corps. His promotion to Lieutenant followed in September 1894. At around the same time, the newly promoted Lieutenant Maling left regimental duty and was sent on a secondment to the Niger Coast Protectorate.

The “Benin Massacre”

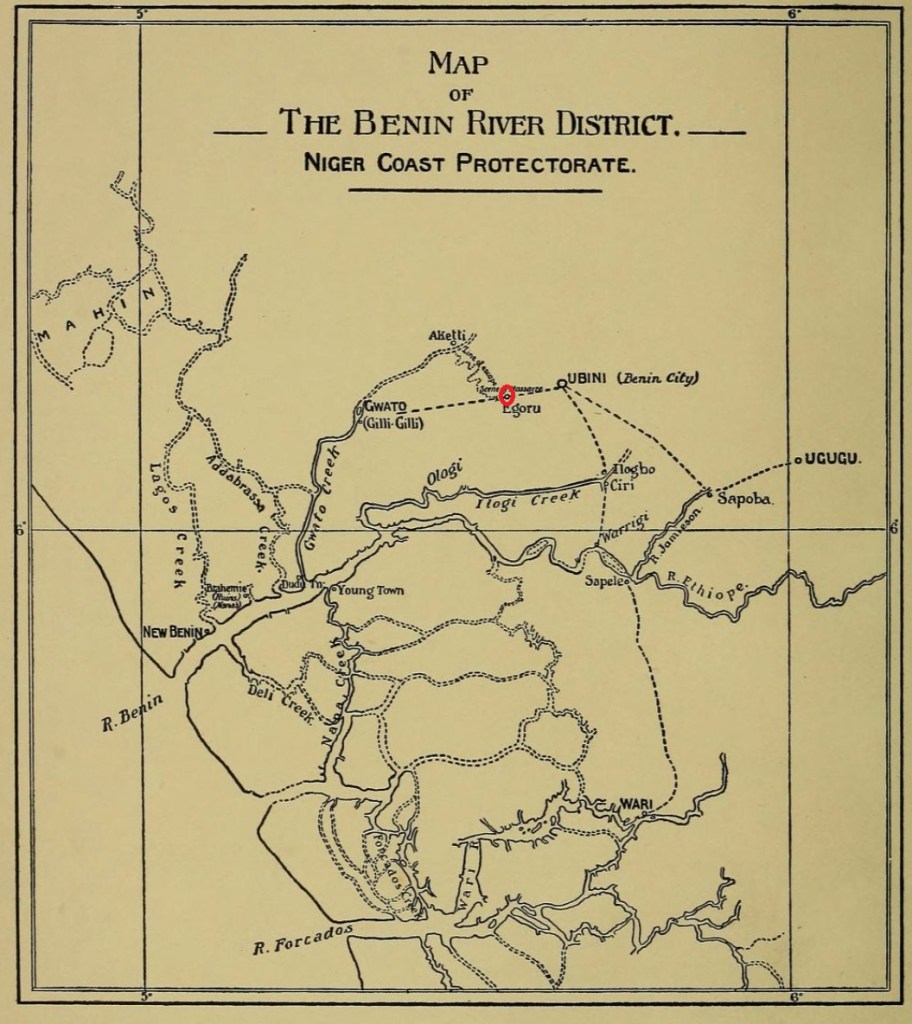

In November 1896 an ill-fated trading expedition to Benin City was planned, under the command of Acting Consul-General James Robert Phillips. The expedition (planned and led by Phillips) set off without authorisation from London to meet the Oba (King) of Benin, Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, in an effort to restart trade in the area after the breakdown of a previous agreement. Phillips had received a message from the Oba, stating they were presently celebrating the Igue festival, and that they were not welcome until after. Despite this, the expedition pressed forward.

Previous attempts had been made to travel to Benin City in 1895 and 1896, but were unsuccessful. Arthur Maling, who had been in charge of a detachment of troops at Sapele had himself been on these attempts, but they were always turned back by Benin City troops.

“On one of these expeditions Major Crawford and Captain Maling landed at Gwatto with a detachment of twenty soldiers and some Jakri carriers. The white men and the soldiers were allowed to come into the town, but any wretched Jakri who showed himself was chased by the Benin City men, and hunted back to the waterside again.”

Alan Maxwell Boisragon, The Benin Massacre, 1897.

Arthur had joined Phillips’ expedition on 30th December enroute at Brass, where he had been on a short posting. Due to his experience Arthur knew the area and people well. In fact, he had become good friends with a Benin City Chief named Mary Boma, whom the expedition stayed with on 3rd January 1897. Sadly this friendship evidently wasn’t strong enough for the chief to give any warning of what was to come, which he surely must have known. On the other hand, the expedition was clearly undesired by the Benin people and they were also there uninvited.

On the morning of 4th January the expedition set off, travelling along a narrow path which forced them into single file. During this march, Arthur Maling was surveying the road as they travelled.

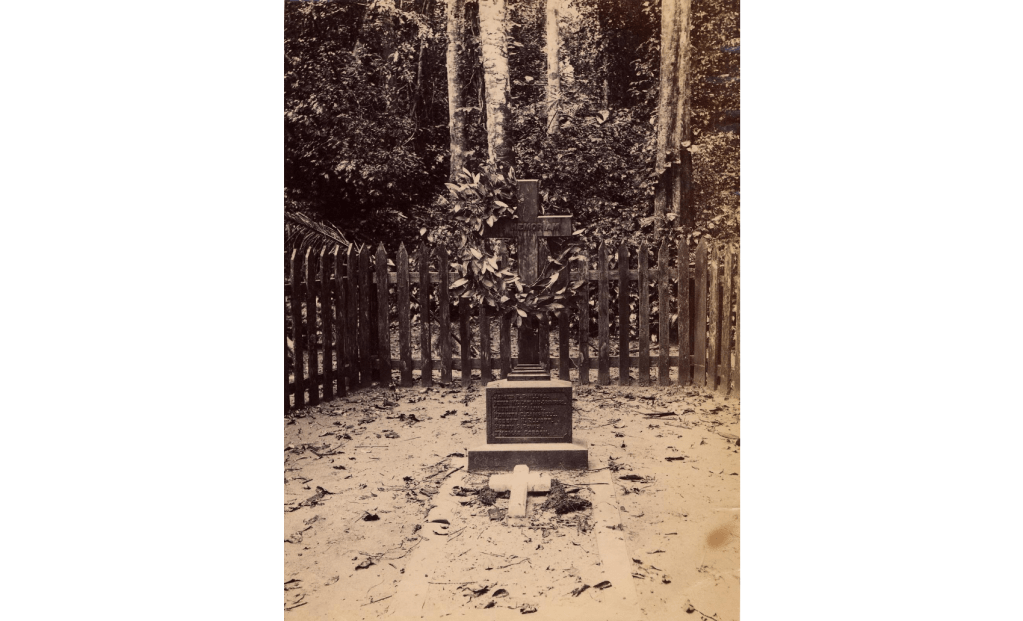

At around 15:00, the expedition were ambushed around Ugbine village near Gwato by Benin tribesmen. The men of the expedition had been unarmed and had no way of fighting back or defending themselves. Seeing an impossible situation, they turned back and headed the way they came, desperately trying to escape. Arthur had been helping to carry another man named Crawford back, and it was whilst doing this that a number of Benin tribesmen snuck up behind them and opened fire. Arthur was hit twice and died shortly afterwards.

Only two British men escaped, Captain Alan Maxwell Boisragon and Ralph Locke. Captain Boisragon went on to write a book about his experiences titled: ‘The Benin Massacre‘.

These events of January 1897 would have a tremendous ripple effect, leading to the Benin Expedition and the sacking of Benin City by British forces. This ultimately saw the end of Kingdom of Benin. Benin City is now part of modern day Nigeria.

Arthur Maling is commemorated in the Royal Memorial Chapel, Sandhurst. It is unknown how this frock came to survive, it had presumably been used by him in India and later. It was possibly returned to his family along with his effects after his death.

Yet another example of how the history of an object can be explored through a little research!